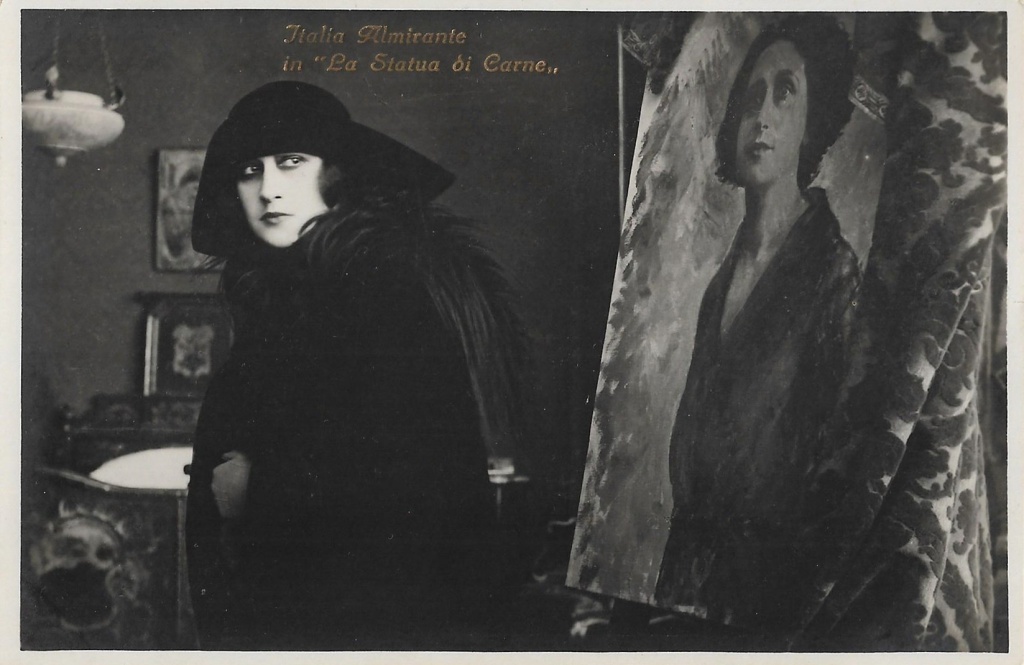

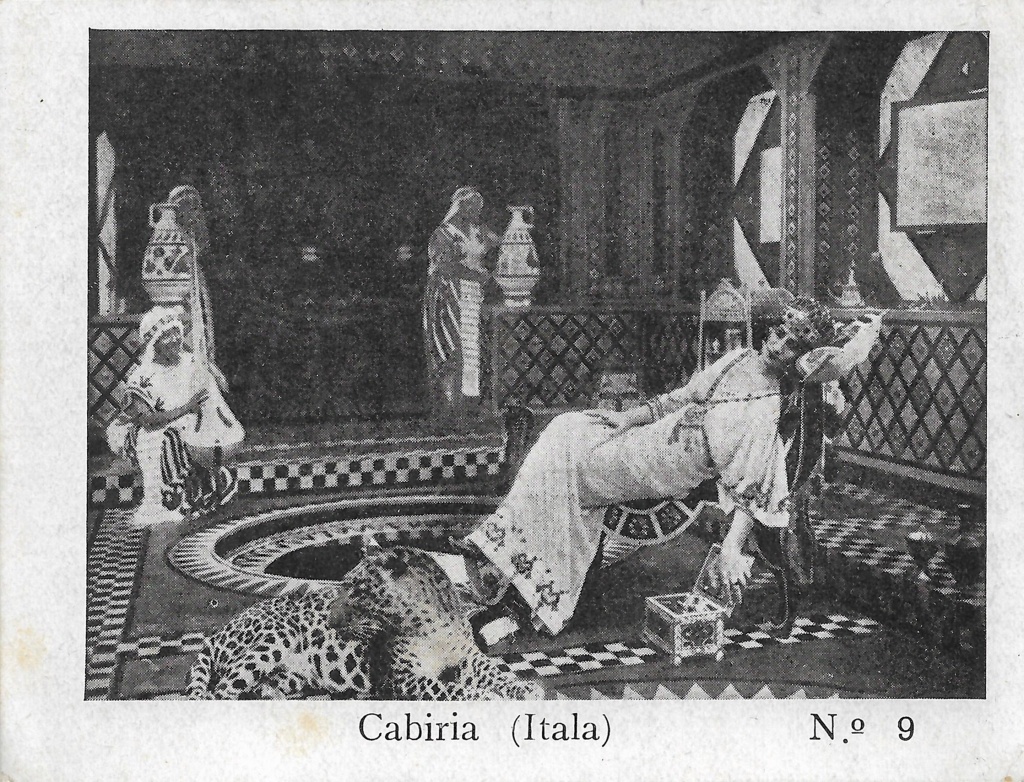

Here is an update on the presentations of my new book, Quo vadis?, Cabiria and the ‘Archaeologists’: Early Italian Cinema’s Appropriation of Art and Archaeology (Turin: Kaplan, 2023). So far, I have given book presentations in October-November in: Pordenone (Giornate del Cinema Muto, 12/10), Turin (University of Turin, 17/10), Rome (Royal Dutch Institute, 20/10), and Amsterdam (Eye Filmmuseum, 3/11).

The presentation in Pordenone was the international premiere and the launch of the extended book trailer (only visible at presentations, in contrast to the teaser on YouTube). Together with two other book presentations, I had a Q&A with the Giornate’s book fair coordinator and host, Paolo Tosini. We had some sixty visitors. Afterward, there was a nice drink at the Teatro Verdi, where I signed various books.

The second edition was in Turin at the Sala Blu of the Palazzo del Rettorato, an impressive 17th century building and the heart of university of Turin. Our panel consisted of e.g. the vice-rector and professor Media Studies Giulia Carluccio and Domenico De Gaetano, director of the Museo Nazionale del Cinema, who both gave welcome words and paid tribute to the book, while Claudia Gianetto (Museo Nazionale del Cinema) chaired the session. Afterward, we had a nice interdisciplinary series of presentations by myself, by Silvio Alovisio on early Italian cinema, transnationality and transmediality, Alessia Fassone on the Museo Egizio and Egyptomania, and Giovanna Ginex on Italian 19th century painters of Antiquity. After answering questions from the audience (among whom experts in film, theatre, art, etc.), we closed off with drinks in the courtyard.

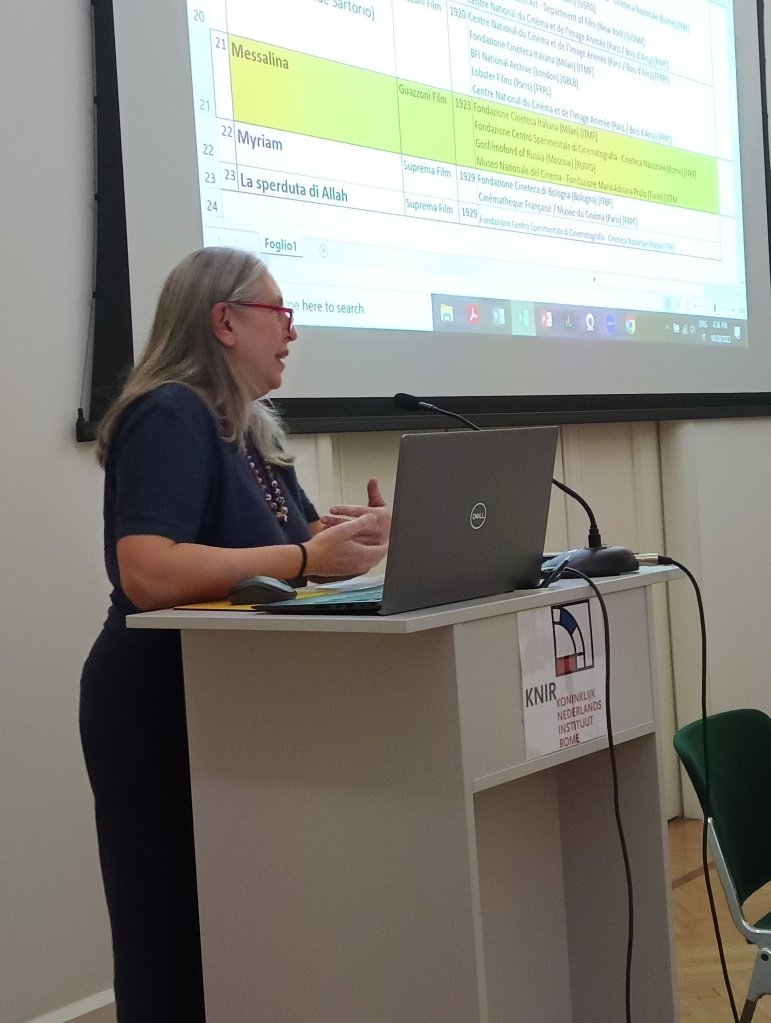

The third edition took place at the Dutch Institute (KNIR) in Rome, which is idyllically situated just outside of the Villa Borghese park, in a monumental villa from the 1930s. Despite a public transport strike and sirocco, we managed to have representatives from all three Roman universities, either in our panel or among the audience. While Maria Bonaria Orban, staff member History of the Institute, chaired the round table, we had a rich mix of disciplines represented, with Luca Mazzei (Tor Vergata) on the historiography of Italian silent film, Stefano Cracolici (Durham University) on cinema of the 1910s as one of transfiguration & belatedness, Monika Wozniak (Sapienza) on Quo vadis in art & popular culture, and Maria Assunta Pimpinelli (Cineteca Nazionale) on the archivist perspective, canon & availability of prints. After my own speech, I offered the book to managing director, Tesse Stek. Also here, we had a merry round of drinks to toast on the book. The round table & presentation was also an excellent way to meet old and new friends in Rome again.

The fourth presentation took place at the Amsterdam Eye Filmmuseum, an institute with which I already have a forty years old relationship, both privately and professionally. After the welcome by Elif Rongen, Head of Silent Film, and me, we had the extended trailer once more (greatly admired and in presence of the editor Machiel Sprujt), followed by an informal Q&A between Elif Rongen and me. Finally, we showed the compilation film film Italia: Fire and Ashes by Céline Gailleurd and Olivier Bohler, which had commentary by Isabella Rossellini, and which contains many clips from the Eye collection (the highest number, compared to other archives). Attendance was massive, over ninety persons, while also the drinks afterward at the atrium were well visited. I signed many books that were sold on the spot and received many positive reactions both during and after the event.

My for the time being last presentation is coming up soon, on 24 November, at the Fondation Seydoux-Pathé in Paris. Here my presentation will be followed by the projection of the film Cabiria (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914), one of the films central to my book.